Mini Mana Tech Stack

As I am embarking on a journey to rewrite the codebase of my multiplayer online RPG Mini Mana from scratch, I wanted to take the time to share details about the tech stack I used to make the game. This article covers the current stack as well as the changes I intend to make.

The game

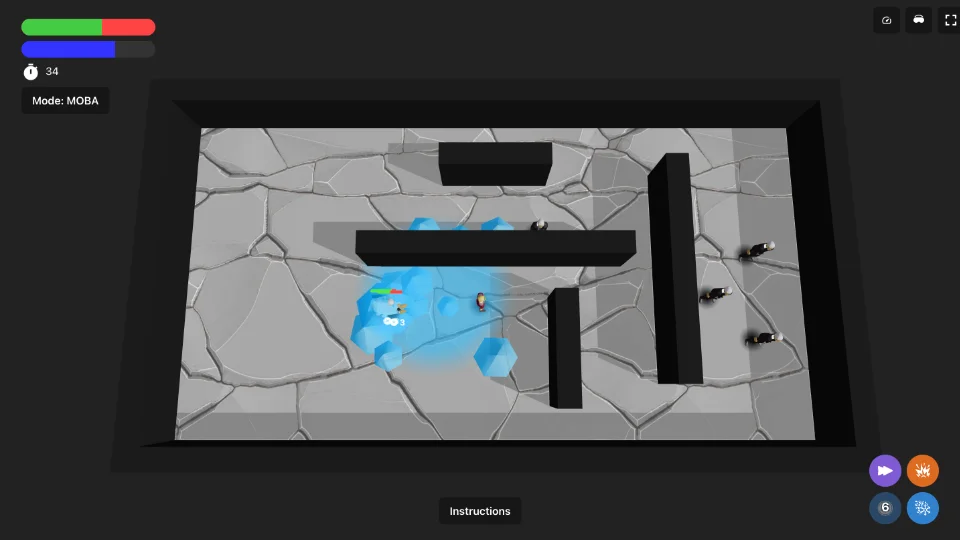

I think the piece of the stack that most people will be interested in is React Three Fiber (“R3F”), which is a React wrapper for Three.js. Before creating Mini Mana, I made 2 small proof of concept mini games using R3F: a tower defense, and a top-down action-RPG, which later became Mini Mana. Here is a screenshot of the proof of concept:

Based on this mini game, it took me about a month of full-time work to release the first version of Mini Mana on WebGamer, which was single-player and looked like this:

I then spent another 3 months adding multiplayer, Hard mode, AI bots, new maps, and 3rd-person support:

And this is pretty much where I’m at now. The game works okay and had a few serious players who finished it and maxed out everything. But there is not a lot of content and I knew that if I wanted to take it to the next level, I would have to build a major “v2” of the game. My main goals with this rewrite are to improve the architecture, the graphics, performance, the multiplayer experience, and to add a lot more content. WebGPU will be enabled by default. The game will be 3rd-person by default and playable entirely solo and logged-out.

General

The Web

Let’s start with the big picture. I am using the web because I find it much more enjoyable than native engines like Unity or Unreal Engine, which I have both tried and built experiences with. The web may not have the performance of native dev, but I’m also not going to make AAA games anyway, so I might as well make stylized games with tools that I enjoy. We have less gamedev-related tools, but we compensate with top-notch developer experience and tooling like instant hot reload, NPM, Prettier, VS Code, etc. I also do not want to invest time and skills into the ecosystems of for-profit companies that can screw me over at any time. The web is the most standard and open platform, runs almost everywhere, is the best option for browser gaming, and web games are extremely easy and lightweight to deploy and put in front of people. It comes with trade-offs, but that’s fine with me.

TypeScript

TypeScript

I am using TypeScript on both the client and server. Using the same language on both sides is very valuable because they can share logic and types. I have systems that run only on the client (the camera follow logic for example), only on the server (AI mercenaries logic), and some that can run on both (physics, spells, enemy AI, etc.).

Tooling

The tools used are pretty classic for web dev: Prettier, ESLint, Jest, VS Code.

Front-end

React

React

On the front-end, I use React for the UI, but most importantly for its composition paradigm and reactivity. I could use Vue or Svelte with TresJS and Threlte respectively, but React Three Fiber has a richer ecosystem with Drei, and I am more comfortable with React. To give a concrete example of what reactivity means in the context of a R3F game, I use reactivity to re-render models when their animations change.

const Player = ({ player }: Entity) => {

const animation = player.usePlayerStore((s => s.animation))

return (

<PlayerModel animation={animation} />

)

}Re-rendering on state changes like this should only be done for states that do not change frequently. Do not re-render at each frame when the position of an entity changes. Instead, move the entity in R3F’s useFrame or in your main loop.

CSS and UI components

The current version of the game uses Chakra UI, but I have switched to Tailwind CSS, Radix UI, and shadcn for the rewrite.

State management

I use Zustand for both global state management and for entities reactivity.

Graphics

Three.js

Three.js

Like the vast majority of 3D experiences on the web, I am using Three.js for 3D graphics as an abstraction over WebGL and WebGPU. I don’t use PlayCanvas because I prefer open-source ecosystems than cloud-based services, and I prefer the single-reponsibility lightweight approach of Three.js over a full game engine like Babylon.js to reduce lock-in.

React Three Fiber

React Three Fiber

React Three Fiber is a renderer for Three.js. It lets you build your scene declaratively in JSX, automatically disposes of resources when components are unmounted, and offers a rich ecosystem of components and helpers via Drei. If you are already a React developer, you will feel right at home with R3F. If you are not, I would recommend learning React first. If you know Vue, use TresJS instead, and if you use Svelte, use Threlte. They are both great and have fast growing ecosystems too.

WebGPU

WebGPU

I use WebGPU in the rewrite. Three.js’ WebGPU support is currently limited, but I want my game to be future-proof and run on both WebGPU and WebGL. Three.js’ Shading Language and Node Materials are unstable and undocumented, so I will not be using any custom shaders for now, only simple meshes, textures, and materials.

Back-end

Main API

My main API is responsible for saving characters, experience, and anything persisted long-term. It’s a Next.js serverless backend hosted on Vercel. I use Next.js instead of Vite for its SSR capabilities, back-end support, and for Next Auth. I use tRPC for my main API for its great TypeScript support and Prisma as my ORM for its TypeScript support and migrations. I use a self-hosted PostgreSQL database.

uWebSockets

I use short-lived real-time websockets servers, which are responsible for running the server-side simulation of a game, broadcasting the server state to clients, and calling the main API for things like updating a character (increasing experience if they kill a monster, for instance). I am not using Nakama or Colyseus for this, just plain uWebSockets servers deployed to Hathora and created on-demand when a player starts a game.

Mini Mana is networked only when playing logged-in, because I didn’t want to use any server for people who just play from the landing page to try the game. So it’s only hitting the CDN and not putting any pressure on infrastructure if thousands of people show up. For this reason, I had to write logic (for instance, casting a fireball) that’s generic enough to either run and get validated fully offline or go through the WS server.

ECS

I use and love Miniplex ECS by Hendrik Mans. For those who don’t know, ECS is a pattern that embraces composition over inheritance to the max. Entities, such as characters or projectiles are just collections of ECS “components”, which can be anything. For example, a generic entity could be defined as:

type Entity = {

faction?: 'allies' | 'enemies'

three?: Object3D

model?: Model

animation?: Animation

rigidBody?: RigidBody

health?: { current: number; max: number }

destroyTimer?: number

}Then, you grab entities based on a subset of components:

const enemies = world

.with('transform', 'model', 'animation', 'rigidBody', 'health')

.where(e => e.faction === 'enemies')Finally, to render your enemies as a React component:

const Enemy = (entity: Entity) => (

<ECS.Component name="three">

<mesh castShadow>

<boxGeometry />

<meshLambertMaterial color="red" />

</mesh>

</ECS.Component>

)

const MyScene = () => (

<>

<ECS.Entities in={enemies}>{Enemy}</ECS.Entities>

</>

)ECS.Entities will re-render enemies when new entities that match the ECS components are added or removed. ECS.Component is a clever React component that will attach the ref of its child to the entity. Here, the underlying Three.js Object3D created by React Three Fiber gets attached to the three ECS component. With this pattern we can render collections of entities declaratively, while controlling their behavior in systems.

Systems are generic functions that are executed in your main game loop and perform work on a subset of entities that match some ECS components. For example:

const HealthRegenSystem = () => {

useFrame(() => {

const entitiesWithHealth = world.with('health')

for (const e of entitiesWithHealth) {

if (e.health.current < e.health.max) {

e.health.current += 1

}

}

})

return null

}Note that systems don’t care if the entities that match are enemies or players, it processes all entities that have the health component. You can orchestrate your entire game with systems like this one. The more generic you can make your systems and components, the better. Mount all the relevant systems to your scene during gameplay:

const MyScene = () => (

<>

<ECS.Entities in={players}>{Player}</ECS.Entities>

<ECS.Entities in={enemies}>{Enemy}</ECS.Entities>

<ECS.Entities in={projectiles}>{Projectile}</ECS.Entities>

<TransformSystem />

<PhysicsSystem />

<HealthRegenSystem />

</>

)Mini Mana being a multiplayer game, I run some systems on the client, some on the server, and some on both. On the server I don’t use useFrame or React, and simply run the plain system functions of specific systems at every tick. Some systems are:

- Client-only: the camera following the player and rendering systems.

- Server-only: that’s most systems, like attacks, aggro, damage, etc.

- On both: Cooldowns, to allow casting spells, and buffs effects.

Since the whole codebase uses TypeScript, code can be shared between client and server easily.

Physics

I am using detect-collisions as a minimal 2D physics engine. In the rewrite, I will have 3D maps with Z elevation such as hills, but the game logic will still run entirely in 2D. I am using detect-collisions both for client-side prediction of collisions and for server-side validation. This way controls are responsive on the client, but validated and corrected on the server if needed.

I am not sending character movement input to the websocket backend but positions directly. The server verifies that the positions are reasonable and repositions players if not. This makes moving around very responsive. So clients get a bit of leeway for moving around, but all other actions (casting spells, receiving damage, etc) go through the WS server first. I do not need a full physics engine like Rapier at the moment, and I prefer a pure JS library to not have to load Wasm libraries asynchronously and to be able to run in any JS environment without Wasm incompatibilities (Jest doesn’t support Wasm for example).

The way I deal with the contour of the map is by creating a polygon that closes on itself. A bit like the shape of your finger if you do the OK sign 👌. This way I never deal with hollow polygons, which can be problematic with some libraries.

Content

Maps

Currently, my maps are created with my app PolyDraw, which lets me draw polygons and export their coordinates as JSON. From these coordinates, I draw the map using Three’s ExtrudeGeometry, but it is buggy for complex geometries. For this reason, and to achieve better graphics, I will be switching to designing maps in Blender.

AI

I use Polygon.js to add “padding” to my map polygon. From this new polygon, I use poly2tri to triangulate it into triangles. Finally I feed those triangles to Nav2d, which generates a 2D navmesh for pathfinding. See what the navmesh looks like here.

Mana Potion

Mana Potion

In parallel of the rewrite, I develop my library Mana Potion, which is a toolkit of helpers to build JavaScript games in React, Vue, Svelte, and vanilla JS. Whenever I need a new feature in Mini Mana, I will see if I can add it to Mana Potion first so others can benefit from it. I am using Mana Potion for browser state, input management, mobile virtual joysticks, and the main loop. Mana Potion gives an easy access to inputs and browser states:

import { getMouse, getKeyboard, getBrowser, useMainLoop } from '@manapotion/react'

const ControlsSystem = () => {

useMainLoop(

() => {

const { right } = getMouse().buttons

const { KeyW } = getKeyboard().codes

const { isFullscreen } = getBrowser()

// ...

},

{ stage: INPUTS_STAGE },

)

return null

}useMainLoop lets you organize your main loop outside of the R3F canvas in a predictable order of stages (such as inputs, AI, physics, rendering, UI, cleanup stages). You could do this with useFrame’s renderPriority option, but it must be used inside of the R3F Canvas.